Unveiling Ariadne; in the wild terrain of the feminine psyche

Throughout history, when dominant cultures subsumed others, they strategically employed the native pantheon underneath their own. This proved an extremely successful way to sway entire nations into subordination as belief systems and worship still shaped society. The process of appropriation of mythological narrative is similar to taking a wild landscape and manipulating its ecosystem with a specific use in mind, often by methods of removal, addition, or reassignment. The landscape changes until at one point, its original contours and details have been obscured and we are no longer aware of what lives beneath the surface. Similarly, colonizer cultures integrated stories while discarding or altering those aspects of deities that did not fit into the dominant mindset. In The Masks of God: The Occidental Mythology Joseph Campbell asserts:

“It consists simply in terming the gods of other people demons, enlarging one’s own counterparts to hegemony over the universe, and then inventing all sorts of great and little secondary myths…to validate not only a new social order but also a new psychology.”

For thousands of years, the European psyche has been remoulded by a narrowing of patriarchal rule building layers of landscape that shaped the way we came to view our goddesses and gods, and by extension, understanding our nature in the spectrum of female and male. By both shaving off those layers and by replanting a story back into its original context, its socio-political and ecological environment, we may assign different meaning to how we understand and experience narratives, archetypes, and ultimately ourselves.

Ariadne as patriarchal maiden

The story of Ariadne arises in ancient Greek mythology. Ariadne is Cretan maiden princess and daughter of King Minos. When King Minos disobeyes Poseidon, God of the Sea, by refusing to sacrifice Poseidon’s sacred white bull at the annual ritual, Poseidon curses Pasiphae, Minos’s wife, causing her to mate with the Bull and birth a monstrous horned child. Minos orders to keep this child out of sight and traps him in an unnavigable labyrinth. Consumed by loneliness and cruel treatment by his father, the child transforms into a flesh-eating monster they call the Minotaur. Every year it devoures the seven youths and seven maidens which were sent to it from Athens. One day, one of those seven youths is the archetypal hero Theseus who volunteers for this mission to save his own kingdom on the mainland of Greece. Ariadne falls helplessly in love with him and shares the labyrinth’s secrets. She gives him a flaxen thread, a shining gold, to help Theseus find his way out after he slays the Minotaur. Ariadne joins a victorious Theseus on his journey home only to wake up discarded on the island of Naxos as swiftly as he had wooed her in the first place. After years of despair, Dionysus, vegetal God of Ecstasy and Love, finds Ariadne and makes her his wife.

Ariadne’s myth proliferates in a time when Goddess worship as the central axis of human society is waning. Goddess worship characterizes as a nature-based cosmology in which all of life is imbued with the same cosmic life force carried by the lunar symbolism of the Great Mother’s triple aspect - birth, death and rebirth. The arising pantheon of masculine monotheism stands in the polarizing daylight of the Sun. Anne Baring (2019) describes this period as the emergence of duality in life and death developed into a fear of nature and, somehow, a need to control and transcend it. The human consciousness that begins to break away from its dependence on nature identifies itself with the sun and the sky gods as a solar principle. The solar myth holds within the transcendent light of the divine as the promise of soul’s transmutation, the unveiling of the inner sun, yet it also denotes another kind of myth; the one which turns against the Great Mother and separates light and dark into opposition. In this solar myth that lies at the core of Eurocentric patriarchy, the solar is hero slayer and saviour who must overcome his deepest fears, master the forces of nature, and continuously strive to reach new goals. This is the hero who will give rise to the patriarchal forces that begin to dominate, shape culture and belief systems. It will annex thousands of years of land-based reverie to establish nature domination while relegating the female and exalting the male. Leonard Shlain points out in his book The Alphabet versus the Goddess, how throughout history in Europe and the Middle East, suppression of women’s rights aligns with suppression of Goddess worship.

The Great Goddess

What makes Ariadne especially interesting as an archetype is that she roots into the soil of Crete, an island of great natural abundance that played a specific role in mythology and history. By 400-500 CE Ariadne is known as princess maiden and lovelorn phantom lamenting her fate. As helpless maiden she became the blueprint for subsequent fables and myths on the feminine, thriving as feeble princess stories who seemed to have no choice but to await a knight’s rescue. This repetitive motive threaded the female psyche into thoughts of powerlessness and false dependency, a form of imprisonment women often voice in the therapy room. But where do the stories we tell ourselves come from? Not everything can be thrown on family and upbringing; we swim in a vast social soup of swirling images signifying unwritten rules, morals and ethics. As in Campbell’s words above, these images are imbedded in mythical narrative, in the bedtime stories we tell our children. The images build on each other to shape the reality we live. Our cognitive ability to create meaningful change co-depends on our ability to move out of these expectations and open up to new narrative, but it takes much less energy to make sense of the world using preconceived images than starting afresh. The gap between what we expect and what is there when we actually look, can be startling. What other story then does Ariadne offer when we step into this liminal space?

A few thousand years before Ariadne turned maiden, she was known as the overarching (Moon) Great Goddess of Minoan Crete. Crete’s Goddess centered civilization of matrilineal descent was known for its equalitarian and peaceful society. It lasted much longer than its neighbouring countries; it carried over into the Bronze Age from the Neolithic while surrounding areas had already replaced the Goddess. Ariadne is believed to have held titles such as ‘Weaver of Life’ and ‘the Potent One’ as a direct descendent of the Snake Goddess. Although this got lost in a baptized Europe that locked the feminine into a passive vessel, we find traces of similar characteristics still pulsating in other cultures. In Hinduism, the feminine as Sakti is the active energy while, Shiva, the masculine principle, is passive. The Sanskrit term ‘Kundalini Sakti" translates as "Serpent Power", both the subtle and vital energy of life. Retracing our steps further down into history, we also find this feminine echoed in the myths of Isis and Inanna. Isis is the active principle both in finding her husband, erecting his penis by sacred magic ritual, finding his body parts when he is cut up by Seth, and embalming him after putting him back together. Through her active principle she re-members him at a point in history when worship of the Solar God began to take over. Similarly, we find Inanna and Ereshkigal’s underworld exchange representing both the passive and active principle, here braided into one by Innana’s death while Ereshkigal births, emphasizing that dark dynamic liminal space of vegetating, incubating and regenerating. Both symbolism and actuality of death as attributed to the (Mother) Goddess was once both revered and feared. It belonged to her lunar aspect in which moon waned and disappeared into darkness to rebirth itself three days later.

As Mother Goddess, Ariadne associates with vegetation, animation, and natural life, but as ‘Mistress of the Labyrinth’ she leads us to the center. The labyrinth symbolizes the underworld, the way to the soul, for in a labyrinth you cannot get lost as all paths lead to the middle, the center, the Self.[1]The way of this path is surrender, typical to the Goddess, and differs from our conquering hero in that the conquering turns inwards. We offer up our own fear to something greater than ourselves. Both the meandering ways of a labyrinth path and Ariadne’s many variations in which she meets death, link her into the later manifestation of Persephone as Queen of the Underworld. Ariadne’s ‘descent’ to the island isolates her from life. In one story she falls asleep and lies next to a guarding Hypnos whose home is the Underworld. In another variation, Ariadne births Dionysus’ child on the island after she is killed, therefore giving birth in the realm of death, much like her predecessor Ereshikhal. Birthing in the underworld is synonymous to a birth of soul.

Ariadne asleep with Hypnos at her side. Fresco from Pompeii.

Downing (2007) motions to look at Dionysus, of whom much more was written down, to know Ariadne better. Dionysus is ‘often called the womanly one’[3], and the one to bring men in touch with their femininity. In embodying feminine sensuality, Dionysus comes to women in their most impassioned moments. He is chthonic phallos, deep and bodily. One of his symbols is the Bull. The Bull as a symbol of fertility belonging to the animistic Goddess stretches back to 60,000 years ago in South African cave paintings and spread its mycelial roots into Egypt as symbol of Osiris and in India to Shiva. Both are two distinct lunar and vegetal Gods known for their connection to the land and animal life. In its first known manifestation, the South African water bovine stood for the omnipotent life force. This also translates as kundalini, chi or mana. Where Dionysus connects man to a primal, relational sensuality, he brings woman into erotic autonomy. Ariadne represents this feminine who lives unafraid of her own sex and sensuality.

The Dynamic Feminine - wild terrain of the feminine psyche

This feminine is dynamic, often associated with untamed lands and wild forests. The dynamic feminine, termed by Jungian theorist Gareth Hill[4] is the realm of wild imagination, the flow of experience, ecstatic embodiment birthed by transformed awareness or chaos erupting out of predictability. The experience of eroticism in the embrace of the Lunar Goddess closely translates to the world as lover, an erotic relationship to the world as found within Hindu culture, early Vedic hymns, but also as the bridal mysticism in Sufism and Kabbalism. This consciousness co-arises in the eroticism of a primal nature of the senses. A bodily shamanic ability to sense and communicate with its more-than-human environment. This consciousness emphasizes the erotic as a relational quality, rather than the sexualization of intimacy. Re-awakening to the world as alive speaks to the ancient Mother Goddess culture that later resurfaced in the gnostic concept of the Anima Mundi, the alchemist term for the Soul of the World. This erotic quality stands in stark contrast to the patriarchal rule which has sought to eradicate this mode of existence by any means necessary.[5]

‘Ariadne’ by John William Waterhouse

Ariadne and Dionysus’ relationship also reveal Ariadne as carrying an androgynous aspect that mirrors Dionysus. The later patriarchal version of Ariadne, the helpless maiden who falls in love with Theseus, will only sustain the promise of the solar hero until she decides to stop waiting for a knight, and picks up her own weapon of choice. A weapon relates to the ability to cut ‘right from wrong’ as a tool of discernment and differentiation. This is what the maiden must learn. Once a woman’s psyche has reclaimed her vitality - vitality meaning life force, but also the sense that one’s actions are meaningfully aligned with a deeper sense of purpose - she has also managed to retract a large proportion of projections onto the men (and women) around her. No longer seeing through inherited perspectives, and embodying a centre of solid stillness within, she comes into her own. She can now withstand, hold and carry through the fertile and the destructive principle of the Great Goddess, the waters of birth and the fire of annihilation, without becoming it. She is active and passive; she becomes the pillar who sustains the bowl of the Feminine, surrendered to a Goddess who does what needs to be done. This face of the Goddess most fierce, best known today as Kali or the Black Madonna as a symbol of the crone,

‘had to be suppressed by patriarchal religions because her power overruled the will even of Heavenly Father Zeus.' She controlled the cycles of life and death. She was the Mother of God, the Nurturer of God, and, as a Crone, the Slayer of God. While Christianity retained the feminine as Virgin and Mother, it eliminated her role as Crone.”[6]

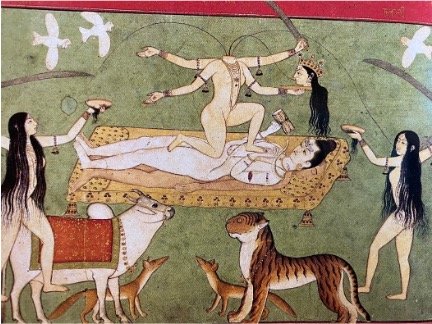

Kali is the final emergence of the great Goddess Durga (Parvati) in her great battle against the demons who, by the desperate plea of the powerless Gods in the face of the masculine demonic, cannot be destroyed by anyone other than Kali. While Kali can also be consumed by her own force of destruction, embedded in her nature lies her relation to Shiva, who in his surrender to her, returns Kali to their unified cosmic dance of life. This type of destruction carries a note of compassion that supersedes the individual in service of the whole, in service of Soul. Such symbolic death as an agent of transformation is reflected by nature’s cycles. Dying in nature is a process of putrefaction and fermentation by yeast and bacteria in which death itself is food for life and rotting matter the cornerstone of a complex ecosystem. After cells have been broken down, decomposing matter starts to purge, a feast for microbials and insects. It soon becomes a hub of activity for all sorts of creatures, and each one links into another. Nothing about natural death destroys relationship; it strengthens it, vitalizes kinship and nourishes the whole.

‘It’s through the Goddess that the creative work is accomplished. She checks the God’s imagination and his creative or destructive mania. She is the intercessor. It is she to whom man must pray. This role of intercession is found in all Goddesses, and even in the Virgin and Christian world. The mother goddess prevalent in prehistoric religions yields gradually to the cult of the lover goddess.[8]’

From Great Goddess to a modern-day heroine: the maiden and the crone

The theme of heroines subverting the antiquated, patriarchal models of the conquering (patriarchal) hero have been surfacing in modern animations of Hayao Miyazaki. Disney has also been changing the narrative of their animus-anima driven plots in the unification of the masculine (prince) and feminine (princess) to favouring the portrayal of independent women as can be seen in Maleficent, Elsa (Frozen I, II) and Vaiana, announcing a new era of a primordial spiritual and psychological narrative. The young women in these stories are feminine and have an androgynous aspect. They require no partner, because they are of themselves, embodied enough to face and receive the Goddess archetype. These women are focused, independent and strong, just like prepatriarchal Ariadne. Their journey requires them to overcome patriarchal constructs that would otherwise overpower them. Although they are challenged to conquer, this ‘battle’ does not require them to kill but rather reabsorb aspects of themselves through uncovering truth, being resilient, intelligent, and reintegrating their instinctual selves and spirit, while surrendering to the call of the unconscious and the feminine dynamics of a labyrinth path. They offer compassionate understanding to their protagonist rather than seeing them as nemesis who needs to be murdered, while also standing firm and unmovable in their convictions of what is right. Convictions that root into humanitarian and ecological justice. We see this arising in the organic and fluid uprisings of young people’s revolutions in different parts all over the world, many carried out by young girls and women. They seek to destroy ideas in order to liberate life. The Indian and Tibetan Ucheyma, a self-decapitating goddess belonging to the lineages of the tantric Buddha Vajrayogini, shows this embedded strength within the feminine who cuts off her false ego for the sake of life. She feeds the world with her blood.

Kangra School, c 18th century, gouache on paper

Throughout the journey, the leading figures of feminist animation are initiated into a deep listening; an ecology of soul that includes the more-than-human world. Their lysis is not to reconnect with a male counterpart, their path weaves the masculine in. Rather, the story leads to a re-seeding into the feminine ground of the Anima Mundi. In these tales the young women are chosen by the Goddess. This choosing by the Goddess does not reflect a singling out of an individual, but more so the relentless and active component of a Goddess who keeps calling, as has often been ascribed to the gnostic Sophia, and the meeting of that calling. She called out to them, and the women responded, however long the journey. We somehow divorced ourselves from this relationship. In the lived reality of patriarchy, Ariadne’s time on the island represents the feminine in deep pain at the loss, not of Theseus, but of her bull brother, and in extension a chthonic way of life. Ariadne’s complexity in her representation of the rise and fall of Feminine consciousness reveals itself more clearly when we look at her actively choosing her fate: it is Ariadne who gives the thread that weaves Theseus into the narrative. Her choice to do so culminates in her own abandonment, leaving her stripped of her ability and strength to find her own way back. By helping Theseus slay the Minotaur, it seems that Ariadne conforms to the ruling patriarchial collective and betrays her own chthonic nature. She denies her body and the earth as sacred and alive, the earth as Anima Mundi. This pain of both abandonment and abandoning feel very much at the core of our human drama, in both men and women, yet there might still be more to Ariadne’s story than this.

Seeding wisdom in times of great need

While Ariadne’s essence as Great Goddess got covered over by layers of patriarchal history, in the archetypal world, we can only bury seeds. Seeds possess the ability to remain dormant in the soil until the right environmental conditions prompt them to germinate. This is how a long-established farmer’s paddock, once shaved from its topsoil, may reveal a field abundant with wild orchids. But the orchids disclose themselves not wholly the same as its parent plant. Seed dormancy is ancestrally initiated by spreading embryos unfully formed and regulated as a responsive process to a changing environment. The capacity of seed dormancy serves as an evolutionary womb for seedlings, establishing itself to be key for subsequent plant diversification.

Ariadne is an ancestral plant of the Feminine rooted in the wild terrains of the animist mind that once lived in Europe. The repeated attempts throughout history to usurp Goddess worship and her inherent feral power started around 6000 BCE. While Ariadne stood firm as a lone surviving Great Goddess in the basin of Old Europe and the Middle East, patriarchal forces ravaged her shorelines, hacking into the rocks that upheld her. Their slaying swords did more than murder a way of life, it was a far reaching sophiacide. When Ariadne made the choice to help Theseus, she abandoned her own story, but did she not also do so because she intuited that patriarchy would last? Did she sense her environment like the plant whose anticipatory action to spawn dormant seeds serves the survival of itself? Perhaps where Ariadne truly reveals herself as a Great Goddess is exactly here. In her act that confirms she is the one who embodies gnosis, a cosmic wisdom of the soil. She is needle, thread and scissors stitching destiny into our reality. Part of Ariadne knew she had to weave Theseus into the story so that he would abandon her, allopatrically separating her, allowing her to remain dormant and resting in the hopeful risk that she would someday form anew. Since then, many fairytale maidens have been put to sleep by the dark feminine - that potent witchy crone - both of whom used to reside in the same Goddess. But today, nap time is over.

[1] Downing, C (2007) The Goddess, mytjhological images of the Feminine, iUniverse, p. 63/64

[2] idem

[3] idem

[4] Gomes, M & Kanner, A (1996) The Rape of the Well-Maidens in Ecopsychology ed Roszak, Gomes & Kanner, p.119

[5] Idem page 120

[6] Woodman and Dickson (1996) Dancing in the Flames, Shambala, p.134

[7] Mokerjee, A (1988) Kali, The Feminine Force, Destiny Books, p61

[8] Daniélou A (1992). Gods of Love and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 78

[9] Vaughan Lee (2016) Spiritual ecology : The Cry of the Earth, The Golden Sufi Center

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: perception and language in a more-than-human world. Vintage Books.

Aizenstat, S. (1997). Jungian Psychology and the World Unconscious. In: A.D. Kanner, M.E. Gomes andT. Roszak, eds., Ecopsychology : restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco, Calif.: Sierra Club Books, pp.92–99.

Baring, A. (2019). The dream of the cosmos : a quest for the soul, Archive Publishing.

Baring, A. and Cashford, J. (1993). The Myth of the Goddess, Penguin UK.

Herschkowitz, H (2019) Vision Magazine Jungian Analysis of Frozen 2: How Disney's Frozen II Reveals the Shift of the Collective Unconscious

Jung, C.G. (1973). The collected works of C.G. Jung. [online] Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Available at: https://vdoc.pub/.

Lerner, G. (1986). The creation of patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

Macy J (2021) World as Lover World as Self, Parralax Press

Roszak, T., Gomes, M.E. and Kanner, A.D. (1997). Ecopsychology : restoring the earth, healing the mind. Sierra Club Books

Williams, B (2021) Rewriting Ariadne: What is Her Myth?

Willis C, Baskin C, Baskin J , et al (2014) New Phytologist: The evolution of seed dormancy: environmental cues, evolutionary hubs, and diversification of the seed plants

Woodman, M. and Dickson, E. (1997). Dancing in the Flames : The Dark Goddess in the transformation of consciousness, Shambhala.